Insights / urban

Can we design for urban equity?

Exploring Transit-Oriented Developments (TODs) as a path towards a more inclusive society

Michael Leong, Deputy CEO|

Wong Lei Ya, Architectural Researcher|

October 2023

Abstract

The idea of urban equity stems from the pursuit of fairness, attained through the levelling of political, social, and economic opportunities. Achieving this is crucial as cities grow; rapid urbanisation, if unchecked, can lead to congestion, pollution, and inequality.

Compact, well-planned cities have shown to lead to better health outcomes, reduced emissions, and lower economic costs. How do Transit-Oriented Developments (TODs) fit into this narrative?

This World Architecture Day, we look at the vital role that TODs play in the creation of equitable cities, as seen through the lens of Singapore’s Northpoint City.

Urban Equity Defined

The concept paper of the World Urban Forum 7 held in Medellin, Colombia, The Urban Equity in Development – Cities for Life, states that there are many different meanings and facets to the notion of urban equity which is growing in importance universally.

The common denominator is that equity relates to fairness, and in order to be achieved, it requires levelling the playing field politically, socially and economically in the local and global arenas.

Urban equity is the end goal of equalisers that level the playing field in cities. They ensure everyone regardless of social and economic status benefits from the resources, opportunities, and prosperity of cities. Due to its compact urban arrangements, city living tends to play up wealth inequalities in society. The Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) typology, however, serves as part of an efficient urban system that neutralises these disparities, paving the way to designing truly equitable cities.

The Institute for Transport & Development Policy (ITDP) highlights that the first step to achieving truly equitable cities is through the mobility component, by taking a “sustainable, equitable and holistic approach” to transit in cities, through the provision of “high-quality, safe and reliable mass transit”. However, it takes more than transit to create urban equity.

A truly equitable city provides not just good transport, but good land use, infrastructure, and amenities that are often overlooked, particular for the poorest communities.

Urbanisation and Inequity

By 2050, 70% or more of the global population will be living in cities. If poorly planned, urbanisation can lead to congestion, higher crime rates, pollution, increased levels of inequality, and social exclusion. Across Europe, healthcare costs of congestion-related dirty air amounts to around $79 billion in lost productivity, diagnosis and treatment of illnesses, and investment in public health3.

The World Resources Institute has found that unequal access to essential infrastructure has a much greater impact on lives, livelihoods, and long-term prospects than differences in earnings. A Belgian study of more than 300 pairs of twins reported that children in “greener” areas had a measurably higher IQ4, while a study in the journal Science Advances found that people with access to green spaces were on average 2.5 years biologically younger than those with limited access5.

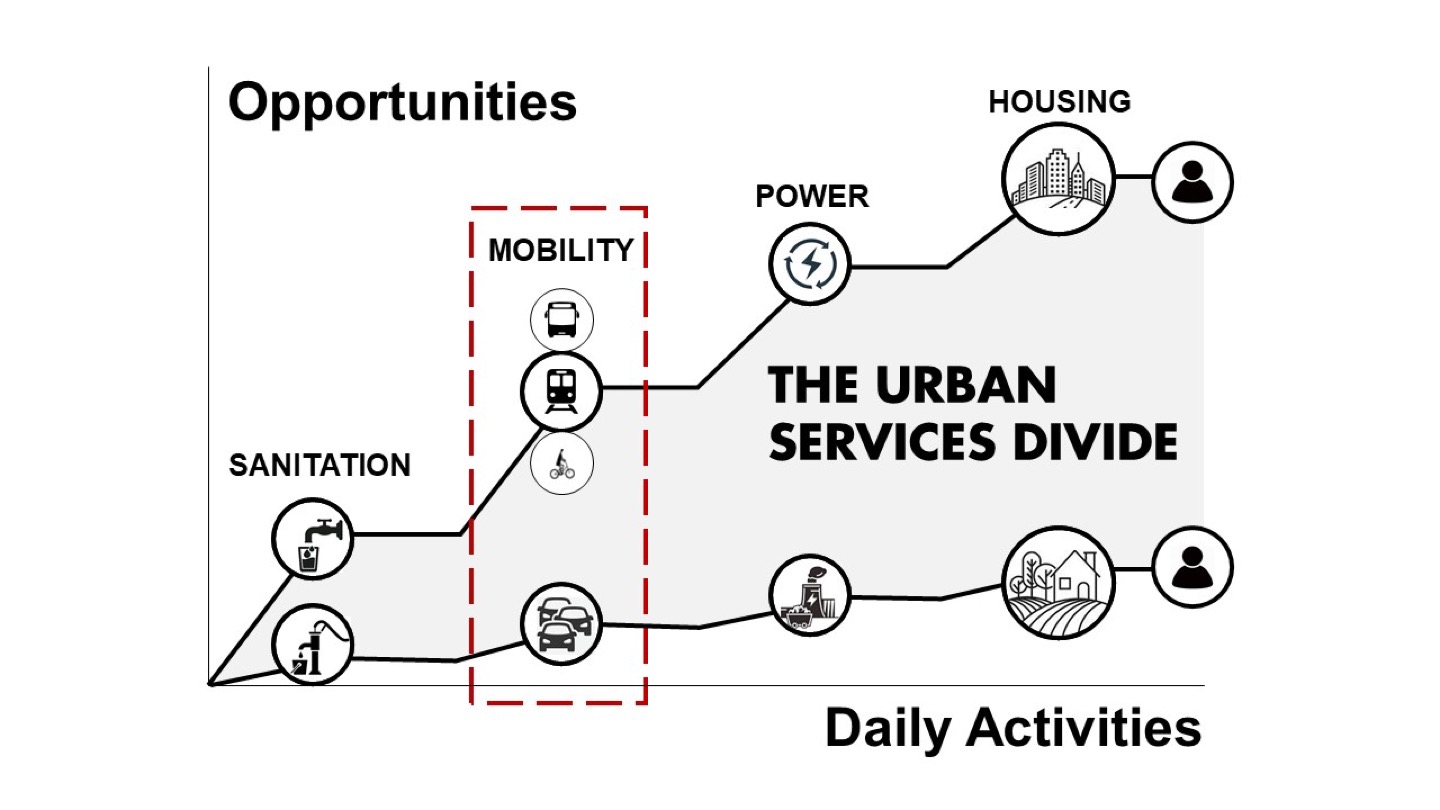

Inequities in access to services impact every aspect of people’s lives. The persistent and growing gap between the experience of the better-served and the under-served has been termed the urban services divide6, where the former have higher and better access to daily activities such as sanitation, mobility, clean and constant electrical power, safe and affordable housing; these translate to better opportunities for productivity, prosperity, and better health, resulting in a better quality of life overall.

Coordinated, Connected, Compact Cities

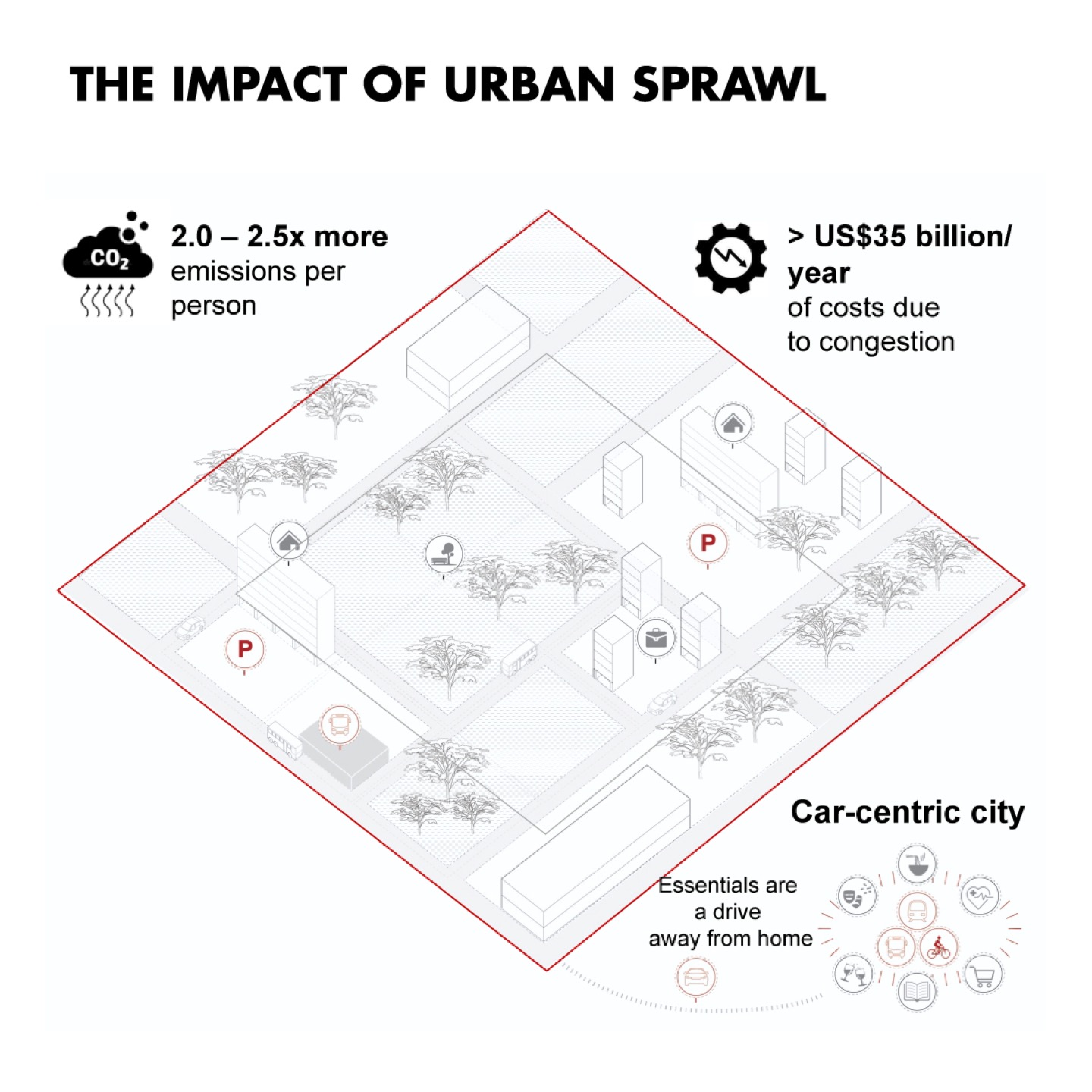

People living in more compact cities tend to have better health outcomes. In the United States, urban sprawl is conservatively estimated to cost around 7% of the country’s gross domestic product7, with 2 to 2.5 times more emissions per person than high-density urban core developments. More than US$35 billion per year of congestion costs are based on lost productivity and health impact.

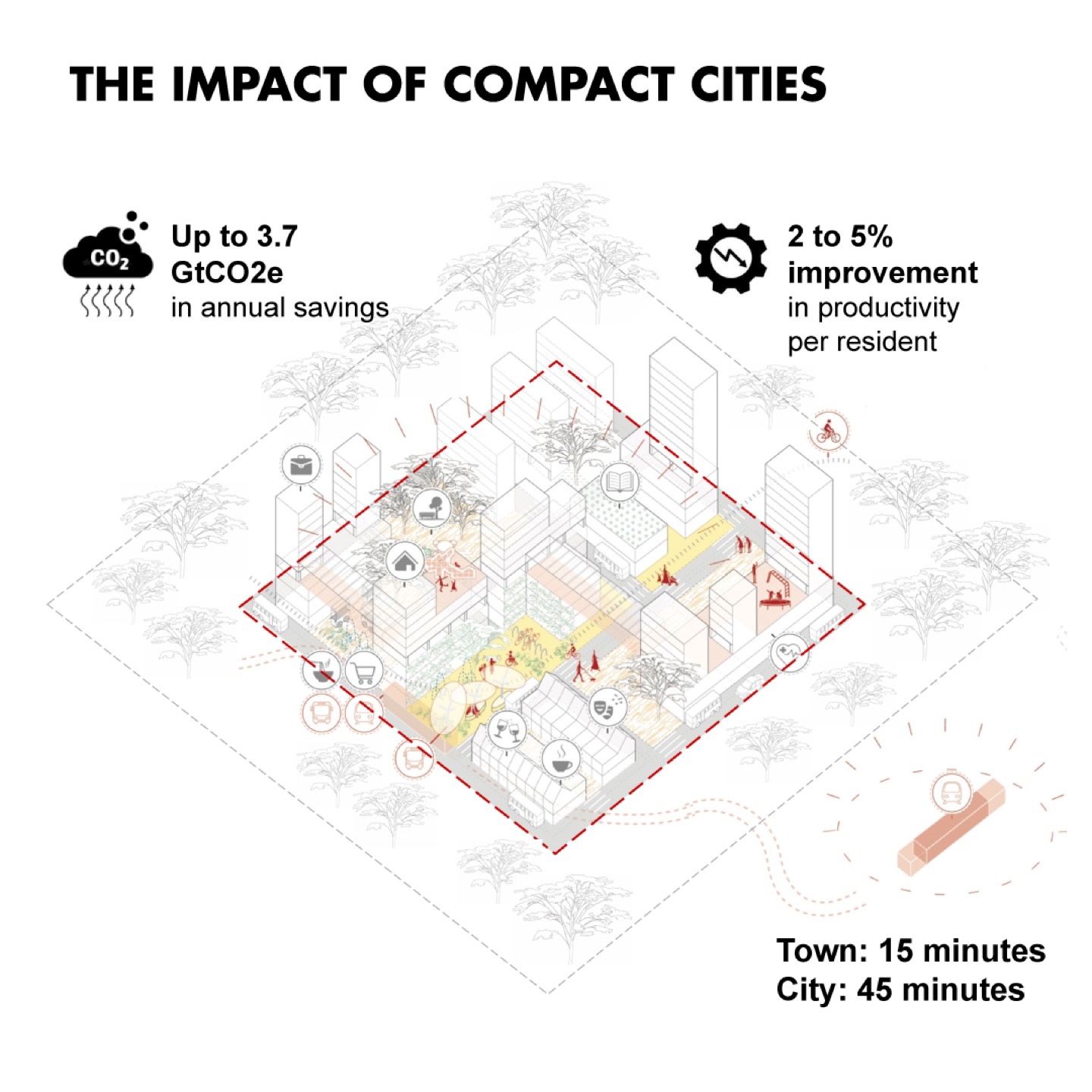

Connected and compact cities, on the other hand, could result in US$17 trillion in economic savings by 2050, with up to 3.7 gigatons of CO2e savings per year over the next 15 years8.

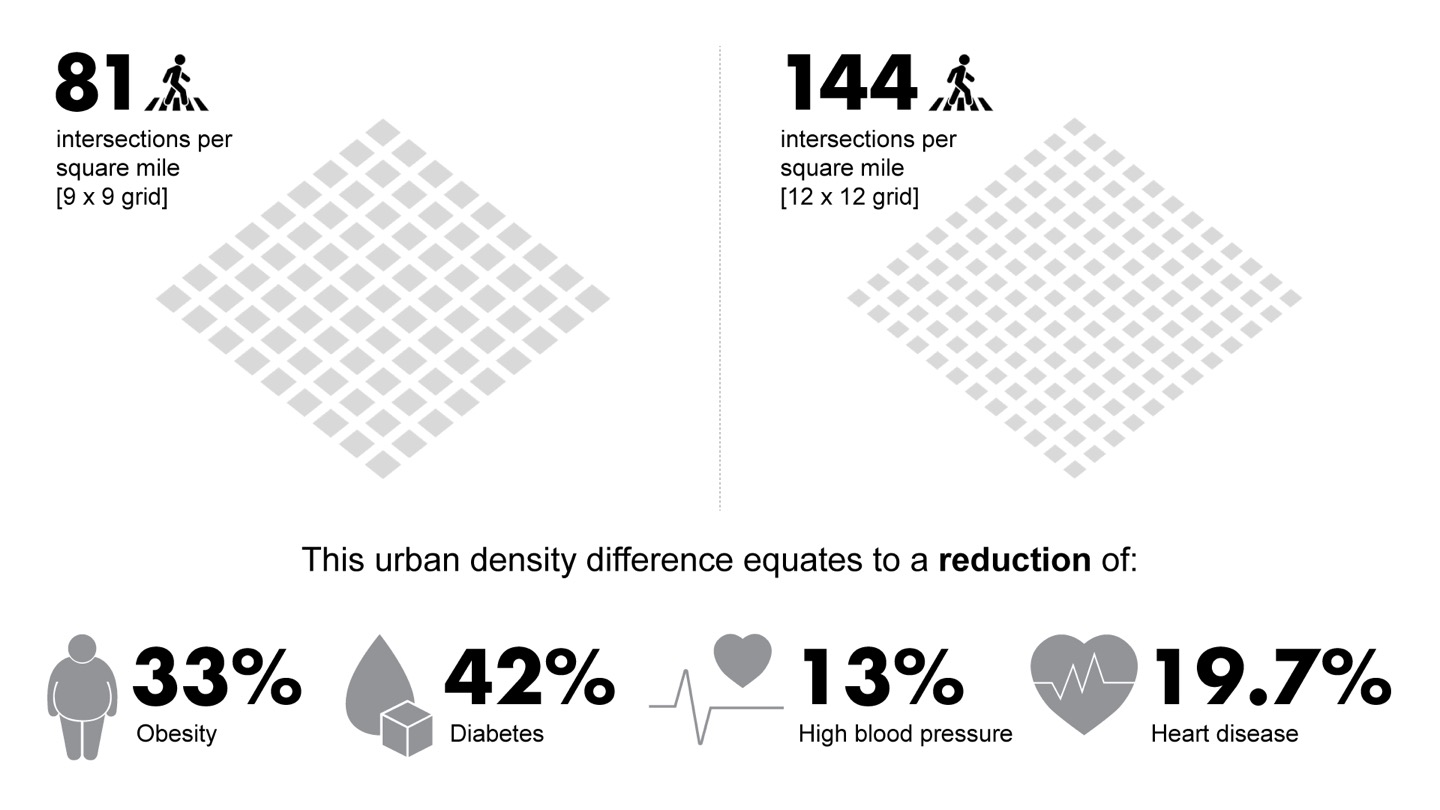

Compact cities with denser intersections per square mile encourage people to walk more, as increased convenience and varied shop frontages make for more interesting and enjoyable walks. According to the Journal of Transport and Health, an urban density comprising a 12-by-12 urban grid with 141 intersections per square mile, when applied across a whole city, improves the health of citizens. Compared to the equivalent of a 9 x 9 urban grid with 81 intersections per square mile, the former results in an overall reduction of 33% in obesity, 42% in diabetes, 13% in high blood pressure, and 19.7% in heart diseases9.

In Walkable City Rules, author Jeff Speck asserts that walkability and “bikeability” are among the most effective tools available to help level the playing field in our increasingly inequitable society10. This lays the foundation for the 15-minute city, which puts home at the centre of urban spatial relationships.

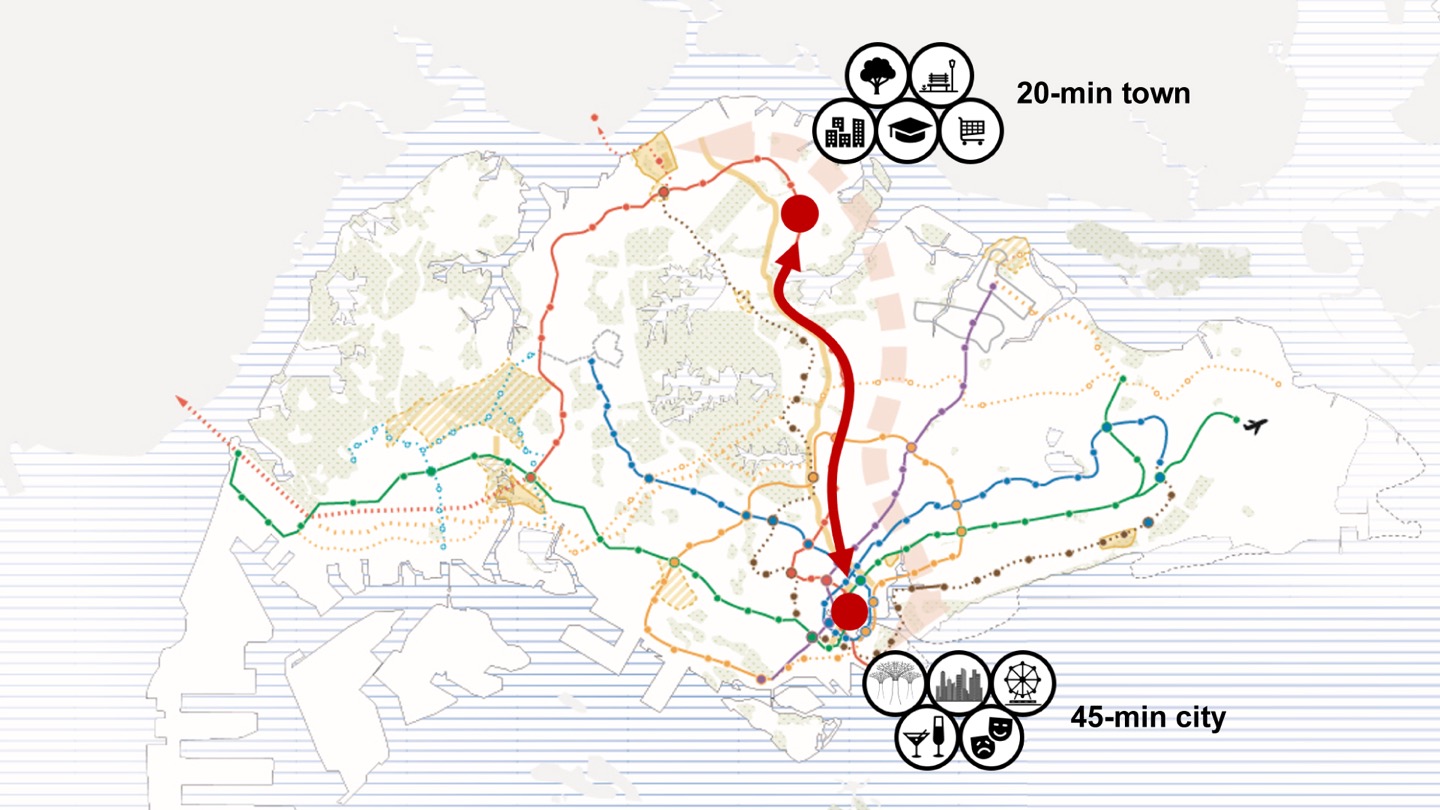

The Framework for an Equitable City

The UNDP’s 1963 report on growth and urban renewal in Singapore11 stated that a prosperous central business district (CBD) must be accessible not only to car owners but to people of all income groups, where low-income earners who live further afield have the accessibility and ability to reach the CBD affordably and quickly. This laid the foundation for the pivotal decision that initiated the mass rapid transit (MRT) infrastructure on the city state. Singapore’s land transport authority developed a route network that integrates different transport services into one unified passenger transport system, connecting people to live-work-play spaces across the island. This long-term planning dates back to the 1960s and has enabled Singapore’s current vision of 20-minute towns, 45-minute cities, where everyone lives in self-sufficient neighbourhoods with easy access to daily essentials, as well as the means to efficiently travel around the city through an integrated transit network.

Mobility, Amenity, and Identity Equity: The Urban Equalisers

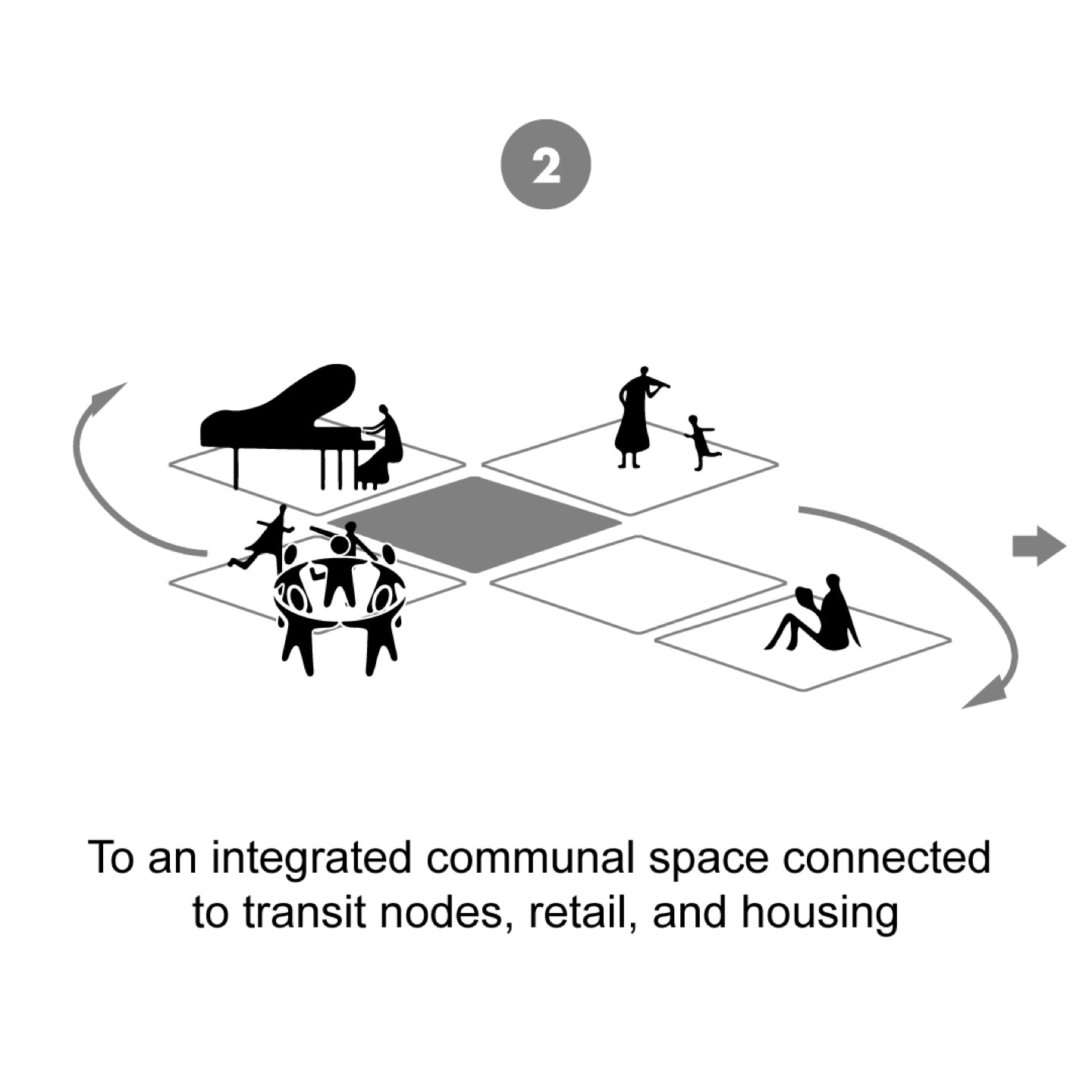

TODs are integrated urban spaces designed to bring people, buildings, activities, and public spaces together through compact city arrangements. Facilitated by an efficient network of multi-modal transit connections, TODs enable inclusive and equitable access to all. We highlight three urban equalisers that are pivotal in shaping the design of equitable cities through the case study of Northpoint City.

Mobility Equity

A Harvard study attributes a person’s commute time as the most significant factor in their plausibility of escaping poverty12. Limited accessibility to reliable and efficient transportation options severely diminishes one’s access to employment opportunities, knowledge institutions, healthcare facilities, and services. This could aggravate structural inequities of health and wealth for low-income communities. On the other hand, a transportation system that achieves mobility equity for all income groups provides access to high quality multi-modal mobility options, achieves a clean and sustainable environment by reducing air pollution, and maximises economic opportunity through enhanced connectivity to places of opportunities13.

Mobility equity in Northpoint City can be seen through interconnected loops that improve connectivity to surrounding areas and transport nodes.

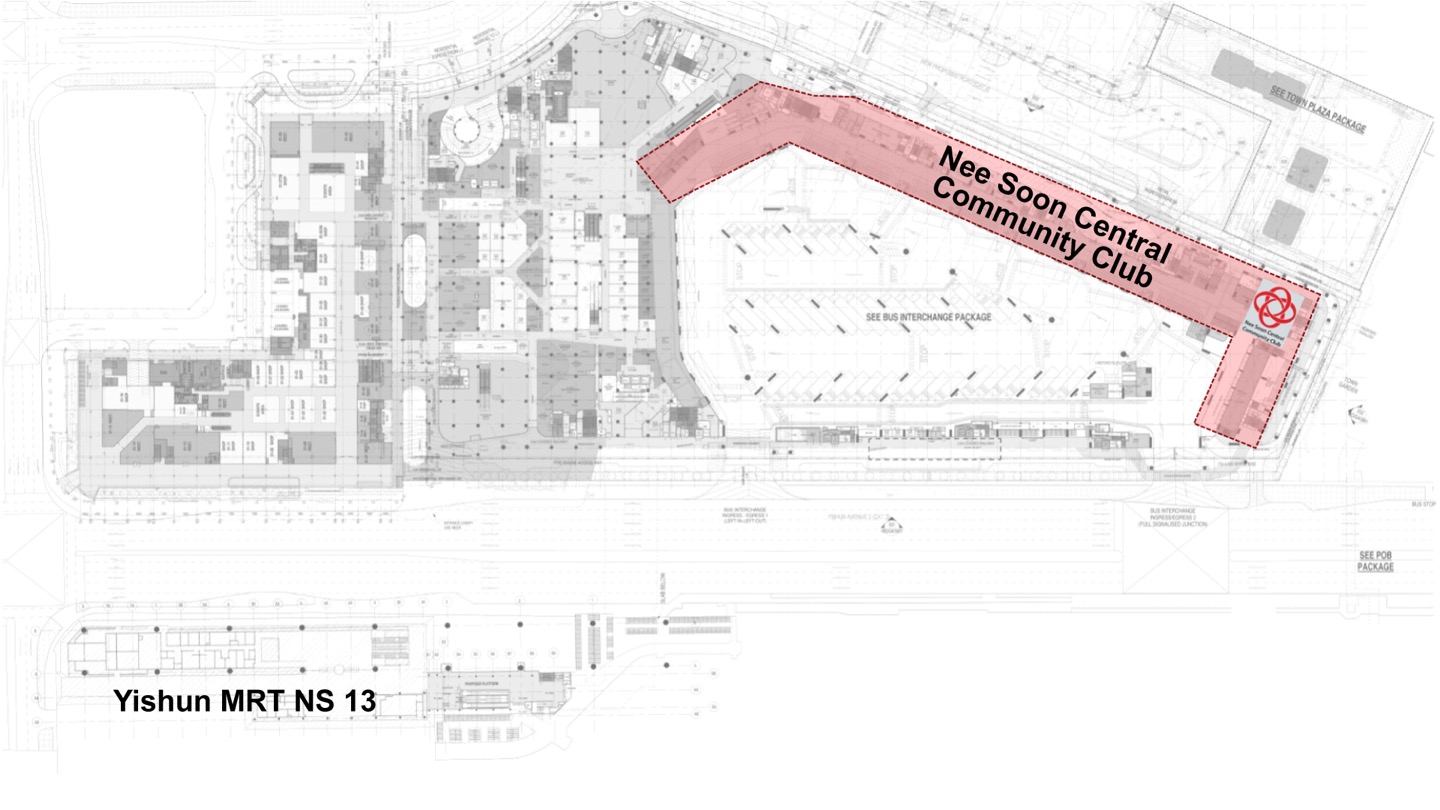

Located at the heart of Yishun Central, the Northpoint City (NPC) project improves upon the existing Northpoint Shopping Centre, completed by SAA in 1992. It integrates within it a bus interchange, Nee Soon Central Community Club (the first community club to be located within a mall), a rooftop community garden with wet and dry playgrounds, Yishun Public Library, and a 920-unit condominium located above the shopping podium.

The concept of interconnected loops improves connectivity to surrounding areas and transport nodes to enhance existing businesses, enrich community activities, and energise community life. Two seamless loops enhance mobility by integrating transit, retail amenities, and public spaces for new residents: A retail loop between NPC and Yishun MRT station, and a community loop linking the mall, bus interchange, town centre, town square, and town garden. Furthermore, these loops extend NPC’s vibrancy to the wider existing Yishun community.

The inter-modal transit hub enables mobility for all by co-locating amenities connected through an integrated network of pedestrian connections of under-ground and at-grade connections, overhead bridges, woven into the wider park connector network (PCN).

These all-weather connections allow one to easily grab their daily essentials along their way home, to work or in-between their commuting transfers. The HeartZone within the Yishun Integrated Transit Hub fosters inclusive commutes that enable independent living among seniors and persons with dementia, allowing them to continue their daily routines and to age well within the community. Other inclusive features include priority queueing and reserved seating areas for persons in need in between bus berths. Connectivity to the existing urban fabric and community is further enhanced by integrating with the existing Yishun Town Centre through a pedestrian link bridge and the town square, allowing people of all abilities easy and quick access to transit services and new amenities. This multi-modal connection widens the options that residents have in travelling to other pedestrian and park connector networks across the whole island, while still having their daily essentials within reach in their existing neighbourhoods.

Amenity Equity

The UNDP’s 1963 report on growth and urban renewal in Singapore11 stated that a prosperous central business district (CBD) must be accessible not only to car owners but to people of all income groups, where low-income earners who live further afield have the accessibility and ability to reach the CBD affordably and quickly. This laid the foundation for the pivotal decision that initiated the mass rapid transit (MRT) infrastructure on the city state. Singapore’s land transport authority developed a route network that integrates different transport services into one unified passenger transport system, connecting people to live-work-play spaces across the island. This long-term planning dates back to the 1960s and has enabled Singapore’s current vision of 20-minute towns, 45-minute cities, where everyone lives in self-sufficient neighbourhoods with easy access to daily essentials, as well as the means to efficiently travel around the city through an integrated transit network. TODs within this urban framework occur at transit nodes, and have been integral in building equitable communities.

“At the heart of it, it’s about meeting these basic needs: You need decent lighting, clear routes that give eyes on the street, increasing the feeling of public safety, public toilets, drinking water. It’s very banal but it really makes a difference. For some it is just nice to have, but for others it’s a necessity.14”

Walkable mixed-use districts have historically been an urban pattern of development. However, the Covid-19 pandemic has turned the “nice-to-have” 15-minute city into an urgent imperative for equitable urbanism, where all necessary amenities are within a short walk, a bike ride, or a public transit trip from one’s home. Access to third spaces during lockdowns also became especially important when people had to stay home in a bid to slow the spread.

Several public green spaces are situated within a stone’s throw away from NPC, providing a multitude of lifestyle experiences: from jogging in larger natural green spaces such as Yishun Park, bird-watching at Yishun Pond, to the more intimately-sized Nee Soon Central Community Park and Yishun Town Garden, to which Nee Soon Central Community Club will have a future connection.

As an extension of third spaces from the larger context, pockets of spaces for social bonding for both public and private users are interwoven within NPC. The design intention of a street-facing lift that extends the common ground to a shared rooftop space that can be made accessible around the clock provides extended access to the public. The playground on the rooftop can be used by both the public and private residents, bringing together children of all economic backgrounds. The importance of third spaces lies in not only providing 24/7 access but also in ensuring the provision of places of pause, such as a variety of seating and quiet spaces for relaxation, a tai chi plaza for communal exercise, as well as essential amenities like washrooms, that are integrated at the rooftop for all.

Pockets of spaces for social bonding and respite for both public and private users are interwoven within Northpoint City.

Great public spaces are not made by design but created by the people who use it. Not only do public spaces need to be available, they need to be carefully activated through placemaking measures to ensure constant usage, as “what attracts people most, it would appear, is other people”15. NPC is the first mall with a community centre that is integrated into it. By rethinking the community centre design and integrating it to a highly accessible inter-modal transit hub, it allows more people to participate in the centre’s activities. Through the design of a naturally ventilated, open-sided sky terrace along the length of the community centre, students and the public utilise the variety of seats and meeting spots provided for quiet study or relaxation in comfort, alongside greenery.

Identity Equity

Before the heavy use of automobiles, a community’s sense of “place” emerged naturally, and was often built around a transit station.16

A solid sense of identity, built on active engagement with one’s community, results in healthier and happier people. Community identity is often times rooted in an attachment to places, based on reminders of heritage and familiar environments17. This involves place identity that distinguishes itself from others in the association of place and people’s daily lifestyles, social interactions and activities that foster a sense of belonging, and walkability that contributes to a safe and vibrant street life. Urban forms need to celebrate place identity and people’s experience to ensure that renewal of public spaces not only improves people’s quality of lives, but also strengthens their sense of belonging over time.

Northpoint City’s façade remediates urban heat with a greener, healthier environment, and cleaner air for active lifestyles.

Despite being rooted in heritage, identity needs to constantly update, rejuvenate, and evolve with the times to stay relevant to both new and old residents. Yishun was one of the three heartland towns selected in 2007 to undergo the Singapore government’s “Remaking Our Heartland” rejuvenation plans — part of the Housing Development Board’s initiative to renew estates to meet the changing needs of the community. This was an opportunity to capitalise on the unique legacy of the site. Heritage markers on the floor of the town square are designed to tell the stories of Yishun’s historical past, while preschool children use the circles during their daily play sessions, integrating heritage into daily lives.

Walkability maximises opportunities for significant social contact by bringing residents closer to each other daily, improving the identity of a place and building more robust attachment amongst the community. Anchored in the Yishun Town Garden, the green necklace activates and enables different activities for all.

Its changing nature shifts from a garden path with quiet study nooks along the community centre, to a lush green façade along the podium and towers, culminating in the rooftop public space with diverse amenities. The feature façade remediates urban heat with a greener and healthier environment for the residents within NPC and from its surroundings, encouraging active lifestyles for the young and old.

TODs: A Foundation for Sustainable and Equitable Cities

Access to urban infrastructure, services, and opportunities greatly impacts a population’s quality of life in a city. It is also a determinant to a more equitable and sustainable future. Despite the inevitable price premium that comes with higher developmental and infrastructural costs, TODs help ensure that efficient mobility options remain affordable and accessible to the masses, allowing every individual the ability to navigate their urban environment independently and safely. The co-location of people, daily essentials, and amenities ensures that such convenience benefits not just residents in integrated developments, but also the wider existing community.

For existing residents, equitable TODs enhance their access to jobs and economic opportunities while supporting local businesses within the neighbourhood. At the same time, TODs strive to retain and evolve a distinctive identity that fosters a sense of belonging among all residents in the community.

The rapid urbanisation that we see around us can only widen gaps between groups of people if socially sustainable development models are not developed and adopted. The TOD model offers an urban solution that is efficient, compact, resilient and equitable.

References

1 UN Habitat. (2014). Urban Equity In Development — Cities For Life. [link]

2 Institution for Transportation & Development Policy. (2014, July 24). This Is What Urban Equity Looks Like: The TOD Standard 3.0 – Institute For Transportation And Development Policy. www.itdp.org. [link]

3 Fleming, S. (2019, February 19). Commuters In These Cities Spend More Than 8 Days A Year Stuck In Traffic. World Economic Forum. [link]

4 Bijnens, E. M., Derom, C., Thiery, E., Weyers, S., & Nawrot, T. S. (2020). Residential Green Space And Child Intelligence And Behavior Across Urban, Suburban, And Rural Areas In Belgium: A Longitudinal Birth Cohort Study Of Twins. PLOS Medicine, 17(8), e1003213. [link]

5 Kim, K., Joyce, B. T., Nannini, D., Zheng, Y., Gordon-Larsen, P., Shikany, J. M., Lloyd-Jones, D. M., Hu, M., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Vaughan, D. E., Zhang, K., & Hou, L. (2023). Inequalities In Urban Greenness And Epigenetic Aging: Different Associations By Race And Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status. Science Advances, 9(26). [link]

6 Mahendra, A., King, R., Du, J., Dasgupta, A., Beard, V. A., Kallergis, A., & Schalch, K. (2023). Seven Transformations for More Equitable and Sustainable Cities. Publications.wri.org. [link]

7 Haddaoui, C. (2018). Cities Can Save $17 Trillion by Preventing Urban Sprawl. www.wri.org. [link]

8 The 2018 Report of the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. (2018). The New Climate Economy. [link]

9 Marshall, W. E., Piatkowski, D. P., & Garrick, N. W. (2014). Community Design, Street Networks, And Public Health. Journal of Transport & Health, 1(4), 326–340. [link]

10 Speck, J. (2018). Walkable city rules : 101 steps to making better places. Island Press.

11 Abrams, C., Kobe, S., & Koenigsberger, O. (1980). Growth and Urban Renewal in Singapore. Habitat International, 5(1-2), 85–127. [link]

12 Chetty, R., & Hendren, N. (2015). The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility Childhood Exposure Effects and County-Level Estimates. [link]

13 Sanchez, A., Creger, H., & Espino, J. (2018). Mobility Equity Framework How To Make Transportation Work For People Environmental Equity. [link]

14 Gardiner, J. (2021, June 17). Can Design Make Cities More Equitable? The Possible. [link]

15 Project for Public Spaces. (2010, January 3). William H. Whyte. Www.pps.org. [link]

16 Gillman, K. (n.d.). How Transit-Oriented Development Can Transform Community Placemaking. Www.crsa.com. Retrieved October 2, 2023, from [link]

17 What Makes Public Places “Ours?” (2014). Arch2O.com. [link]

© 2024 SAA Architects Pte Ltd. All rights reserved.